Mari Oshima’s “Unlimited” is on view in Paper Reveries, a show at the Shirley Fiterman Art Center of the Borough of Manhattan Community College in Lower Manhattan. The show runs until February 9, 2015. See Mari Oshima's page on our website.

December 11, 2014

Mari Oshima at Shirley Fiterman Art Center

Mari Oshima’s “Unlimited” is on view in Paper Reveries, a show at the Shirley Fiterman Art Center of the Borough of Manhattan Community College in Lower Manhattan. The show runs until February 9, 2015. See Mari Oshima's page on our website.

October 31, 2014

Kang Hoodoo

A Note on Zulu Painting.

As it happens I have an appreciable Zulu painting by Todd Bienvenu now hanging in the stairwell of a Park Slope double-wide. It is a brown and creamy splotch of a thing, with lots of subtle greens and blues, and it goes with the colors of the brownstone. It looks as if a house painter used the canvas for cleaning brushes, and left some of his own thoughts as well. A wonderful wipeout of a painting, full of deft brushwork and slights of hand.

|

| Todd Bienvenu, Stooges, 2013 |

Stooges, by Todd Bienvenu, deserves a great foyer in a Brooklyn mansion somewhere. It's fitting for reception areas, a mischievous "whatever" with a humorous tone. Cool and welcoming, and tasteful. Brownish and creamy shit-colors and throwaway chicken guts comport beautifully with the patina of any distressed hardwood interior in the borough. It is a painting that lends itself to furniture, as furnishing, for the location, for the occasion. A polite, decorative painting, and also snapped like a table cloth from under a banquet. Exceedingly well juggled, and all wrapped up in a mud-ball of brownish baroque. Just a big beautiful rumpus of a painting that doesn't care what you think.

It was serendipity that just as I finished installing this painting in the Greco-Victorian hallway of the building, there appeared Basquiat and the Bayou at some "Confederate Museum" in New Orleans.

In that moment it hit me like a coconut on the head ... that there really is such a thing as zombie painting, or voodoo, or Zulu painting, whatever you want to call it. It is a subculture in painting that excels at what an art critic might euphemistically call "canceling maneuvers" or "abject expressions of defiance or refusal" or simply "insouciance."

|

| Jean-Michel Basquiat, King Zulu, 1986 |

|

| Robert St. Brice (20th cent. Haitian) signed, oil on board, Voodoo face, 29" x 25" Robert St. Brice was one of the very few first generation Haitian painters who was totally unique. His brand of voodoo expressionism straight from his psyche is totally unique and powerful. So much so he was the inspiration or father of the Saint Soleil genre that is in such demand today, but still no one painted like St. Brice. From this website. |

|

| Stooges, Installation View |

Todd Bienvenu's work is by no means limited to the zombie theme, he's not some goth obsessive. He is better known for his lurid scenes of American life, wrestling, girls, beer culture, and so on. We just happen to have a few gems at the gallery from his earlier and more abstract zombie phase. "Stooges" is looking for placement in a top-notch residence anywhere in the city. "Spitfire" is a high note in Bienvenu's zombie period. In one bullseye after another his work covers an ample range of human experiences and foibles.

|

| Todd Bienvenu, Spitfire, 2013 |

|

| Todd Bienvenu, Spitfire, 2013, Detail |

Two years of Todd Bienvenu in Bushwick is already a national treasure, a pristine document in style and place of a reviled and envied hepitude. Bienvenu's world is usually presented as an allegory, where the "great white trash" of America stands in for a pastural meditation, like an old dixie rococo painting, upon what is really a complex urban life. Since my gallery has a history with this painter, I can only say we are soon to be safely in the dust of his career, I'm sure. This painting, Stooges, is that dust perhaps. It is a premier brownstone hallway painting, a glorious splotch, stylishly replete with astringent maneuvers in abstraction and figuration. The painting is all cancellations and cross-outs, a lateral dive across language ... with zombies. And it coheres, it hangs together in its localized drama, and in its very human stain as painting.

|

| Stooges, Installation View |

|

| Donald Baechler, Untitled ("globe"), 1984 |

A brutal moment leaves a skid mark on the document of painting. Donald Baechler and Rick Prol may not have been zombie painters, or they may have been at one time or another, I don't know. They might as well have been, I don't care. By zombie painting I do not just mean some special instance of outsider folk art. Rather, I mean the insult carried from outsider folk art into the avant-garde, as a deliberate strategy. This dodge does not come only under the sign of the zombie. Though it comes often enough under that motif, it is really one of several related strategies that pertain to art as resistance.

Several painters in the East Village in the 1980s detected a fault line between the "visual culture" of the postmodernists, and the "visuality" that was preferred by the old school painters. They tore up that fault line. They decided to insult painters and conceptualists in one go. Hoodoo painting is one example of this trend from the strange afternoon of the East Village scene. Strong icons are needed to rattle the cage of painting, and there is nothing in the universe of aesthetic experience quite like the rooster-strut of a Haitian or a Bayou zombie. It is a treasured vernacular of the American continent.

|

| Rick Prol, I Have This Cat, 1985, acrylic on canvas, wood, and glass, 96 x 93 in. |

"If painting is dead, well then, here's a painting of a zombie."

— Todd Bienvenu, 2013

This, by the way, is zombie criticism. It has no real existence. I represent Todd Bienvenu, I sell his work. And so of course I like it. Obviously I am a big fan. You may call this is an advertisement. All the same, important announcements about the artist are in order. Someone must note that Todd Bienvenu is teaching in Louisiana right now, just as the Basquiat "bayou paintings" go on exhibit there.

John d'Addario in his piece in Hyperallergic informs us that the Mississippi had a powerful imaginative influence on Basquiat, a Brooklynite of Haitian and Puerto Rican parentage whose actual experience of the US South was limited. Todd Bienvenu comes from Louisiana with Cajun roots. And these two American painters bare comparison, I submit, and have said in the past, in that each is a trenchantly original painter of zombies.

Zombie aesthetics are folk art entangled in the ganglion of fine art. The zombie is the atavistic feature of a discourse; the twitching of the insensate. It is the chicken man in Blue Velvet. It serves to rend the wall of intelligibility. What Basquiat and Bienvenu, and Prol and Baechler do is to acknowledge unintelligibility in art. The painting is the document of a mistake, and the artist is ready to abandon art as the critics do. That is, in haste, with Adorno, and just as readily. And I like a painting that has no scruples about such things.

— Ethan Pettit, 31 October 2014

|

| Todd Bienvenu, Zombie Apocalypse, 2013 |

Inventory and Prices for Todd Bienvenu

Artist's profile on this site

artist's website

The Gatorman Cometh – portrait of the artist as a young zombie, May 2013

more on Bienvenu in our gallery notebook 2014

Labels:

abstract painting

,

basquiat

,

brooklyn

,

bushwick

,

donald baechler

,

figurative painting

,

hoodoo aesthetics

,

new orleans

,

rick prol

,

todd bienvenu

,

voodoo painting

,

zombie painting

October 30, 2014

I'm the only hell my mama ever raised

The thing I love about this painting, is that we have a girl who is sixteen? Absolutely beautiful and stubborn white trash. She already knows she doesn't have to live here. She knows she can waltz out into the big world any day and get plenty for what she's got. That's not the problem. The problem for her at this point is just how to make the first move.

I'm the only hell my mama ever raised, Todd Bienvenu, 2014

Labels:

expressionist painting

,

hoodoo aesthetics

,

new orleans

,

new york school

,

painting

,

todd bienvenu

,

voodoo painting

September 29, 2014

Full House East - Reception This Friday

Our long-running group show was initiated by David Rich and Paulette Myers-Rich in St Paul Minnesota back in July as Full House West. The show migrated to our gallery in Park Slope Brooklyn in early September, and it will remain up until November 2nd.

Labels:

abstract painting

,

alkemikal soshu

,

barbara lea

,

david rich

,

ethan pettit gallery

,

gili levy

,

jeanne tremel

,

jim denomie

,

marcy rosenblat

,

patricia saterlee

,

robert egert

,

sonam rinzin

,

st paul mn

,

todd bienvenu

August 21, 2014

Thangka Painting with Sonam Rinzin Starts Sept. 20

Starting Saturday, September 20th, renowned artist and teacher Sonam Rinzin will be giving classes on the Tibetan art of Thangka painting and drawing at the gallery in Park Slope, Brooklyn. See details here.

July 11, 2014

Full House West - Opens July 25th in St. Paul, MN

Full House West, a visual dialogue between painters from Saint Paul, Minnesota and NYC, brought together by Paulette Myers-Rich and David Rich, opens on Friday, July 25th. This show coincides with Full House (east), which will commence in August and run through September 2014 at ethan pettit gallery.

June 16, 2014

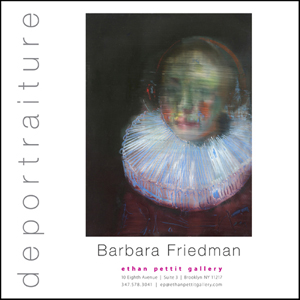

Barbara Friedman - Closing Party

Please join us on Sunday, June 22, from 6PM-midnight, at a Closing Party for Barbara Friedman's show DEPORTRAITURE.

Location details are here.

June 5, 2014

KB in Venice

Pool Cue Archery Bow Cello from 1981, is one of a large group of Ken Butler's pieces now on display in Art or Sound, a survey that spans four centuries of musical instruments and curiosities.

The mere fact that the esteemed founder of "Arte Povera" Germano Celant has chosen to put Ken Butler in any show is a cause for comment, never mind what the show is about. As it happens this is not exactly an Arte Povera show, but rather an historical survey of musical objects from over the course of four centuries. It is, however, a bit of a curatorial "spill" in the manner of Arte Povera. Very old decorative artifacts and sundry pieces of Weimar whimsy are rolled out into the company of objects from the historical avant-garde.

Antiques are pressed into the service of conceptual art, and all the objects in the show concern "the relationship between art and sound" or the "iconic aspect" of musical instruments. Never mind the context or the century of origin of anything, there is a theory that carries them all in a Prada handbag, whose foundation is sponsoring the show. So it is a good chance to see some beautiful and interesting objects from all over the map, and some really dull moves from the 1970s as well.

Adolphe Sax, Natural Trumpet, 1866–84, brass

But I will say this, Ken Butler's hybrid visions stand up to an Adolphe Sax trumpet or a dazzling old street organ, as much as they stand out against the stylistic uniformity of most of the avant-garde and postmodern representation here. Butler really is a new species in the art world, and in Venice it shows. His work has old world charm, and it looks and feels snappy in the generally mortified acres of assemblage art of our times.

I'll venture that Butler's work is the lynchpin of this show. His work is historically sensitive to the older artifacts. It responds to the antique functional objects as well as it does to the newer and patently art historical pieces. And what's more, Ken Butler's instruments are thoroughly and all about the confluence of objects and sounds.

Musical Chairs, roto-picker (for 8 chairs and channels) concept drawing 23.5 x 18 in. 2005. See enhanced album of these drawings.

Rifle Cello, exhibited at Test-Site in Williamsburg, early 1990s

Art or Sound, June 7 - November 3, 2014

Labels:

arte povera

,

avant-garde music

,

conceptual art

,

downtown music

,

germano celant

,

gordon matta-clark

,

hybrid instruments

,

ken butler

June 3, 2014

Unhurried Antinomies – the work of Alkemikal Soshu

|

| The Matador oil on canvas 30 x 59.5 in. 2012 |

Alkemikal Soshu speaks of reconciling opposites, and not just opposites but antinomies, of fundamentally irreconcilable things. His paintings are accretions of such things, compacted strata of the difficult and unwieldy, all splayed out.

Alkemikal Soshu's profile on this website

Alkemikal Soshu – Inventory and Prices

|

| The Benign Snotty and the Discovery of the God Particle oil on canvas 23.75 x 35.75 in. 2012 |

The paintings remind me of the great Alfred Jensen, who is very well regarded in Brooklyn, for his joinder of non-objective painting and conceptual art, of color and the occult, and for certain mapping tendencies. Soshu’s work reminds me of that oblique tunneling that took place in Brooklyn more than three decades ago. The handful of painters in Greenpoint at that time were influenced by such as Jensen, and also by their socratic mentor James Harrison. It was a moment of esoteric abstraction, during the avalanche of postmodern imagery. These were the origins of Brooklyn’s myriad world of painting today. And it just seems right that a painter of Soshu’s temperament should choose Brooklyn as his frame of reference. Or rather, in the case of Soshu, as a substrate to be catalyzed.

|

| Pipe Mandala pencil and ink on paper 30 x 22 in. 2012 |

Soshu lives in Kathmandu, he has never been to the US or much outside the subcontinent so far as I know. His entrance upon the Bushwick and Williamsburg scene has been brazen, obstinate, opinionated, and entirely by way of facebook. Yet an entrance it most certainly has been, and I am strongly of the opinion that Soshu’s is a bracing contribution precisely to the art scene that he has chosen to engage and to which he was drawn from afar.

His early work of more than about five years ago was inflected by what he calls the “low brow” movement, a kind of international brew of comic, decorative, and graphic art. With surprising speed, and in relative isolation, he put together a fighting palette. The shrewdness of this maneuver impressed me. Irony and panache were achieved that take many a New York artist a decade to achieve. This is thinly veiled by the Himalayan flavor of the paintings, and even that is a conceit. a conceit, no less, that confers mordant humor and originality to Soshu’s canvases.

|

| Hermaphroditos Salmacis oil on canvas 26 x 26 in. 2012 |

Hermaphroditos Salmacis involves the Greek myth of the nymph Salmacis, who raped Hermaphroditos, the beautiful son of Hermes and Aphrodite. The “union” transformed Hermaphroditos into an androgynous being from whom the word hermaphrodite derives. Writes Soshu:

The mystical derivation would be the belief in holistic transcendence by a union of opposing energies. A completeness and synthesis of opposites. Aphrodite is associated with beauty, Hermes with literature and poetry. Hermaphroditos is the outcome of both, but in male spirit. I think Salmacis is the integration of the female in the symbolism.

|

| Venom oil on canvas 30 x 30 in. 2013 |

Soshu’s canvases are densely coded, and there are high-pressure zones that gather around matters that need to be “sorted out” as Soshu is fond of saying in the clipped Britishism of the region. This kind of deliberation over a painting is a delight and a relief to me. There is an unhurried generosity here that is appreciated.

— Ethan Pettit, May 2014

May 19, 2014

Deportraiture: Recent Paintings by Barbara Friedman

May 3, 2014

BLASTA! - a thought about allegory in immersive art

Vlasta Volcano, Signs Along the Road, at Art in General, 1993

A good friend who is Serbian brought to my attention early this year, a piece made by Vlasta Volcano some 20 years ago for a show at Art in General about Yugoslav identity. I must say the "Yugoslav identity" dimension of the work was lost on me when I first encountered it in photos. Volcano was a member of the Immersive scene in Williamsburg, and so my initial response to this work of his was from that perspective. Here’s what I wrote about it almost a year ago:

1992 to 93 was a very dark time in Yugoslavia, and there were a number of Serbs and Croats in the local art scene. As it happened I fell in with that crowd for a while. My friend Jelena Tomic is Serbian by way of Paris, I introduced her to my old friend Ivan Kustura, who is Croatian and a painter whom I knew from a circle of Greenpoint artists in them mid-80s. And soon we were drinking at Teddy's with eight or nine other Yugoslavians.

They are figures, like Rodin or Giacometti, except they appear in abject material in a desolate place. From the bubbling coils of melting rubber, phantoms peel out and spring to life ... on a ghetto beach, oh brave new world. From an artist's hand, light of touch, comes a first-rate exposition in Vlasta's work of a certain ... insouciant minimalism of warehouse art of the time. A very simple process, burn rubber tires on the waterfront. A regular fine art foundry. And why not. If you can manufacture art in shops and factories, it stands to reason that you could make art at the ass end of industry as well, from the refuse. Off the schmelting rubber come leaping lords and hipstresses. Vlasta did not draw or paint, he lit a fire, and he caught our shadows all the same.

— Ethan, January 6, 2014

1992 to 93 was a very dark time in Yugoslavia, and there were a number of Serbs and Croats in the local art scene. As it happened I fell in with that crowd for a while. My friend Jelena Tomic is Serbian by way of Paris, I introduced her to my old friend Ivan Kustura, who is Croatian and a painter whom I knew from a circle of Greenpoint artists in them mid-80s. And soon we were drinking at Teddy's with eight or nine other Yugoslavians.

Vlasta Volcano, from photos taken between 1990-93.

Volcano is Serbian, and I knew him the way people in close art communities know each other. That is to say, like family, even though we rarely ever spoke with one another. It might be like that in a Serbian village as well, with someone you've never spoken to, but have known for a thousand years. In a big-city avant-garde, you have people from all over the world, who know each other implicitly.

I do recall one funny exchange with Volcano at a subterranean club on the Southside of Williamsburg called El Sensorium, some 20 years ago. Sub-maritime as well, bulging with aquaria, waterfalls, unearthly lighting, dry-ice vapor, and Volcano was wearing a strip of duct tape over his mouth for most of that evening. At some point I caught him without the tape, and I asked him if he thought the phenomenon of fame and celebrity might be an evolutionary precursor to some form of social telepathy that might become highly articulated in another 40 thousand years or so.

“Could be” he said.

Volcano was, after all, an early proponent of transhumanism, in Brooklyn and Belgrade, which are both places where transhumanist aesthetics took shape in the early 90s, concurrently with the philosophical development of transhumanism in California. Volcano was a founder of the group Floating Point Unit, a major branch of Immersionism, and he always struck me as a most chill and immersive sort of dude. I called him “Blasta.” But I am only now decades later connecting with this artist’s work and its position in the Brooklyn movement.

I gather this work is made from burnt or unraveled automobile tires. And it is Rodin-like, in is morphogenic release of energy and material. It is exemplary immersive sculpture. A calculated manipulation of the concrete random. No arty trappings or skills known to the genres. A process shall be deployed, upon such material as is readily available. No rules of the minimalists are broken, and an appreciably different world from theirs is revealed.

In 1998 Craig Owens located the “allegorical impulse” within minimalism and material art, and extended that impulse to the postmodern art that followed. The immersive artists are also allegorical, but they absorbed this irritating chestnut from the history of art in a different way. Brooklyn artists generally turned away form the analytic approach of the 80s, and discovered the synthetic approach. And so, where the allegory of Robert Smithson or Robert Morris is astringent and literate, the immersive sculpture of the 90s can be saturated with allegory and downright baroque. It must be noted, many thousands of people experienced immersive art first as entertainment.

Lauren Szold was making her seminal immersive work in Williamsburg in 1990 and 91. When I interviewed her at that time, she spoke about meaning embedded in raw material. She said she tried to avoid obvious cultural references; loaded objects and symbols plucked wholesale from the culture. It is characteristic of a lot of immersive work that narrative is ingrained in the material and the process, but not forced through symbolism. Dennis Del Zotto's polystyrene structures come to mind, as does the “plastic fog” of Frank Shifreen at the Flytrap in 1991. And of course many of the schemes of Lalalandia are exemplary in this regard.

The catch here with using the word “allegory” in this connection, is that this word has a precise meaning in literature and art. It means to tell one story by means of another. Usually, this means to recover some aspect of the past, of history usually, and pitch it as a new “story” that can be comprehended by a present-day audience. Napoleon as Caesar for example. But when we get into modern uses of “allegory,” the concept has been harnessed to other similes. Allegory is a resilient and flexible attribute of aesthetic experience; it may not always appear in a sharp “this-for-that” formulation. Allegory may be mixed in with the aggregate, so to speak, of a morphogenic and immersive art.

Volcano's work here is an example of allegory in immersive sculpture. It clearly suggests a lively narrative space, but it just as easily can stand for nothing but process and material.

Volcano, early- to mid-90s, with friends. Brooklyn or lower Manhattan. Photo by Megan Raddant

Labels:

brooklyn

,

dennis del zotto

,

fakeshop

,

floating point unit

,

immersionism

,

lauren szold

,

pseudo

,

vlasta volcano

,

warehouse events

,

we live in public

,

williamsburg

,

yugoslavian artists

April 26, 2014

Deportraiture – Barbara Friedman

Recent paintings and drawings

April 20 - June 29, 2014Barbara Friedman's profile on this site

|

| Big Collar 1 oil on linen 60 x 48 in. 2014 |

|

| Big Collar 2 oil on linen 60 x 48 in. 2014 |

|

| Big Collar 3 oil on linen 60 x 48 in. 2014 |

|

| Portrait of Gertrude van Limborch (after Thomas de Keyser) oil on wood 24 x 18 in. 2014 |

Over the past two years I’ve parked my easel at the Brooklyn Museum, often in front of Thomas de Keyser’s portrait of Gertrude van Limborch (1632). When I am there I paint my own versions of the portrait, letting my rendition verge on disappearing, or else allowing some features to spring into focus, in a way that threatens to make the source unrecognizable.

These “versions” of the de Keyser contain a trace of Gertrude van Limborch’s face. She is the touchstone for any variations I produce, as the subjects are in other portraits from that era. My purpose in working from these old paintings is to serve both their makers and their subjects: not just to bring de Keyser back into view but van Limborch too, and every other person now long dead who was lively and aware when the painters portrayed them.

Another presence is my mother, who used many aliases during her eventful life. It was only after her death that I discovered that as a child she went by the name Gertrude. She invented so much about her life that her adult existence became a distorted portrait she had painted of herself, barely showing the girl Gertrude she had started out as.

One prominent feature of many of these paintings is the Dutch ruff collar. This was a big starched and pleated collar, a style that lasted from about 1550 to 1650. A “pinwheel” around the neck, the ruff was also used on sleeve cuffs. The discovery of starch allowed ruffs to be formed in elaborate figure-eights. The ruff held one’s head up in a haughty pose, aristocratically, with obvious appeal for wealthy Europeans of the time. Queen Elizabeth I wore a ruff, but she issued decrees that limited the size and even the colors of ruffs that could be worn by commoners outside the royal court. In some of the newest paintings from this series the collar is extremely exaggerated.

Although these paintings still riff off my museum studies, they play more aggressively with scale and color, and bring the ornate ruff collar into the territory of gender, class, and body issues.

— Barbara Friedman, April 2014

|

| Portrait of Gertrude van Limborch Thomas de Keyser (Dutch 1596/97–1667) at the Brooklyn Museum |

|

| Cropped Gertrude oil on linen 48 x 16 in 2014 |

The “portrait” has been Barbara Friedman’s idiom of choice in recent years, and yet portraiture is only one dimension of what the critic Lilly Wei calls, without exaggeration, a “formally inventive” approach to painting. These are instinctive and erudite paintings, and they summon a formidable range of strategies. Friedman sets up her easel in museums and pretends to copy the old masters, a trope she associates with “lady” painters. Then comes a subtle but unrelenting process of distortion, destruction, and recovery.

Friedman is a professor at Pace University, a resident of lower Manhattan, and a veteran of the East Village scene. I met Barbara a few years ago when she visited our showroom in Bushwick. Soon after that she became represented at our gallery, and since then she has also showed at Valentine, Studio 10, and Storefront Ten Eyck. Her unearthly portraits have cast a prolonged gaze into this inscrutable demimonde. They are tuned to the habits and the jitters of people who prowl the galleries of Brooklyn and downtown at the present time. And this quality sets them off, distinguishes them as a keen synthesis of painterly and temporal issues.

We are thrilled to be opening Deportraiture on April 19th, a large show of Friedman’s recent work. This show will occupy the front and back rooms of our gallery, it is a thorough display of the work of a painter who has already made a strong showing in Brooklyn. We are honored and proud to host this show, and I hope you will join us for the opening.

— Ethan Pettit, April 2014

|

| Portrait of Gertrude van Limborch (after Thomas de Keyser) oil on wood 24 x 18 in. 2014 |

|

| Portrait of a Dutch Woman oil on linen 48 x 46 in. 2014 |

A Ruff Meditation

Ethan Pettit

The salient of that febrile mind that tossed and turned between the afflatus of Shakespeare and the appearance of Isaac Newton, was the ruff collar. By some accounts an article of fashion not to be outdone until the 1970s, it was a sartorial pinwheel that couched the head and doubtless gyrated to Kepler’s laws of planetary motion.

At the dawn of empire it sprang from the throat. “Sooner may one guess who shall bear away The Infanta of London, heir to an India,” wrote Donne, than one may guess, “What fashioned hats, or ruffs, or suits next year our subtle-witted antic youths will wear.”

They wore the ruff for about another twenty or thirty years, until the middle of the 1600s. It was an Elizabethan accessory that survived the Thirty Years War, the Eighty Years War, the Civil War, for it was laden with starch. The ruff went out of fashion as the scientific awakening began, but long before the time of the Bach family and the awakening in arts and letters that is still with us, or should be.

In the Meditations Descartes says not simply that he thinks therefore he is. Had he said only that he would have vanished. He says more poignantly that he exists because he can be deceived. If all that he knows and feels is suspect, then he is deceived. But for something to be deceived there must be something to deceive, hence something exists. Here is the astringent reduction, the first picture of the “thing that thinks” which Spinoza would rehearse as well somewhat later.

Most careful attention must have been paid to the head when it had lost trust in its body and the world around it and knew not yet what laws governed bodies in the world. Hence the accordion that unfolds from the neck and buffers the brain in a provisional sphere.

And even among the protestant divines of New England, with their immensely complex interior lives, you find that radiant countenance framed in the ruff. Though here the broad flat collar largely replaced the ruff, still it is on the first governor of Massachusetts. On John Smith of Virginia it is, shockingly, as bizarre as the headdress of Powhatan.

It was in the other Dutch colony, the one north of Flushing Avenue, that Barbara Friedman’s unearthly portraits drew attention to the reflexes of the picture-viewing public. It was an unnerving appearance. And in this new range of portraits her distortions are joined to a beguiling anachronism, a separation of the head by a device from the far side of the modern repertoire, and which sweeps away with not a little pomp all of the tropes that are supposed to populate a canvas.

The salient of that febrile mind that tossed and turned between the afflatus of Shakespeare and the appearance of Isaac Newton, was the ruff collar. By some accounts an article of fashion not to be outdone until the 1970s, it was a sartorial pinwheel that couched the head and doubtless gyrated to Kepler’s laws of planetary motion.

At the dawn of empire it sprang from the throat. “Sooner may one guess who shall bear away The Infanta of London, heir to an India,” wrote Donne, than one may guess, “What fashioned hats, or ruffs, or suits next year our subtle-witted antic youths will wear.”

They wore the ruff for about another twenty or thirty years, until the middle of the 1600s. It was an Elizabethan accessory that survived the Thirty Years War, the Eighty Years War, the Civil War, for it was laden with starch. The ruff went out of fashion as the scientific awakening began, but long before the time of the Bach family and the awakening in arts and letters that is still with us, or should be.

In the Meditations Descartes says not simply that he thinks therefore he is. Had he said only that he would have vanished. He says more poignantly that he exists because he can be deceived. If all that he knows and feels is suspect, then he is deceived. But for something to be deceived there must be something to deceive, hence something exists. Here is the astringent reduction, the first picture of the “thing that thinks” which Spinoza would rehearse as well somewhat later.

Most careful attention must have been paid to the head when it had lost trust in its body and the world around it and knew not yet what laws governed bodies in the world. Hence the accordion that unfolds from the neck and buffers the brain in a provisional sphere.

And even among the protestant divines of New England, with their immensely complex interior lives, you find that radiant countenance framed in the ruff. Though here the broad flat collar largely replaced the ruff, still it is on the first governor of Massachusetts. On John Smith of Virginia it is, shockingly, as bizarre as the headdress of Powhatan.

It was in the other Dutch colony, the one north of Flushing Avenue, that Barbara Friedman’s unearthly portraits drew attention to the reflexes of the picture-viewing public. It was an unnerving appearance. And in this new range of portraits her distortions are joined to a beguiling anachronism, a separation of the head by a device from the far side of the modern repertoire, and which sweeps away with not a little pomp all of the tropes that are supposed to populate a canvas.

|

| Portrait of Gertrude van Limborch Thomas de Keyser (Dutch 1596/97 - 1667) oil on canvas, 1632 |

|

| Gertrude with Green Collar on Red oil on linen36 x 27 in. 2014 |

| |

|

|

| Big Collar 4 oil on linen 60 x 48 in. 2014 |